Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Curabitur eleifend tortor nec augue pretium

As the first person ever to be awarded an OBE for services to green banking, Dr Rhian-Mari Thomas is one of the UK’s leading authorities on financing the transition towards a net-zero and nature-positive economy.

However, for some people, the phrase ‘green banking’ is an oxymoron, with financial institutions often viewed as enablers of the climate and ecological crisis – providing insurance for fossil fuel projects and investing in polluting industries, for example.

“But it’s a lazy trope to say they’re just evil or greedy,” Thomas counters. “The fact that money hasn’t moved into some of the areas that science tells us it has to is because there are genuine obstacles in the way.”

As CEO of the Green Finance Institute (GFI), she helps break down these barriers to create enabling environments where private capital can move at pace and scale towards solutions to the crises we face.

When two worlds collide

Prior to her current role, Thomas spent almost 20 years at Barclays working in various departments at the bank, but she had long harboured an interest in sustainability. “My father taught me about the greenhouse gas effect when I was a teenager, and I grew up in a home where we talked about the environment a lot.

“As a student, I spent a year in industry looking at different types of materials that could be used to create fuel cell stacks for electric vehicle battery technology, so it’s something I’ve always been very interested in.”

However, it was only in 2016 when she attended a conference on sustainable finance that Thomas found her calling. “I saw all these people bringing those two worlds together – it was a real eye-opener. I decided there and then that this was what I wanted to get involved in professionally.”

Armed with a PhD in physics, and 20 years’ experience as a banker and an environmentalist in her private life, Thomas was well prepared for her role at the GFI, which was founded in 2019.

“At the time, there was a lot of focus on regulation, disclosures and compliance, and I think people assumed I would take the organisation in that direction, but I decided to try to do something pretty bold.

“Mark Carney [former Bank of England governor] had done an amazing speech on how climate change is posing a systemic risk to the financial sector itself, and how we’ve got to find a way of shifting risk perception. Rather than greening the financial sector, I said, no, I’m going to try to do something which could be complementary to that, which is financing green.”

The green convenor

She describes tackling environmental issues as like “cutting through a raspberry swirl”, with many intertwined problems that must be resolved involving numerous stakeholders.

This is where the GFI comes in, bringing together policymakers and finance experts with civil society and industrial experts to devise solutions to the problems at hand.

“We found a gap where different groups weren’t talking to each other,” she says. “We take very specific problems and work through them until we can find a solution and get more money.

“We’ve done it with sustainable aviation fuel, road-charging infrastructure, nature; ultimately the goal is to create new asset classes and new opportunities for the financial sector to invest in. If we want them to stop investing in things that are bad for the planet, let’s give them alternatives.”

She explains how banks might be reluctant to invest in a sustainable aviation plant, for example, because of concerns related to feedstock risk and supply of municipal waste from local authorities, and the threat of airlines going bust.

“But none of these things are insurmountable; it’s just difficult to know who will account for the risks. You could set up a vehicle with a number of airlines and energy firms, which will buy the fuel through a new organisation, and the banks will then be comfortable with that risk because it’s diversified.”

Real-economy outcomes

Green mortgages, local climate bonds and property-linked finance are just a few products and solutions that the GFI has had success in bringing to the UK market in recent years.

Indeed, green mortgages – which offer preferential terms if a buyer can demonstrate that their property meets certain criteria, such as specific EPC ratings – grew from four products in 2019 to 61 in 2024 under Thomas’ watch.

The GFI is also advising the government on its new £7.3bn National Wealth Fund, with Thomas chair of an independent taskforce overseeing its structure and implementation as it looks to support public–private financing partnerships.

“When looking at first-of-a-kind infrastructure, such as hydrogen projects, it’s quite difficult to finance those things because there’s no track record; no performance data,” she says.

“The people that invest are normally the infrastructure funds, but they’re looking at this opportunity and saying there’s too much early stage risk and that they don’t know if the technology works, so we’ve got to try to solve that.

“But we’ve seen a lot of outreach from the chancellor and the secretary of state for energy security and net zero, who have gone to great lengths to demonstrate their connectivity with the finance and business sector.”

Carrot and stick

However, Thomas explains how raising catalytic capital is not the only challenge, and highlights how legislative issues or regulations can also present stumbling blocks. She describes policy as “the enabler that allows finance to become the facilitator”, adding: “We don’t need billions from the public purse.

“What we need are the de-risking efforts – it’s the policy, the subsidy, the taxes; basically looking at what’s happened with the Inflation Reduction Act in the US where investment in green technologies is up 22% year on year.

“Nearly all of the main banks have signed up to net-zero targets by 2050 so, in principle, the capital is there. What is stopping it moving is that the risk-adjusted returns quite often don’t work and the political enabling environment isn’t there.”

That’s not to say she is opposed to greater regulation and compliance, having been a member of the Taskforce on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures and co-chairing the launch of the Taskforce on Nature-Related Financial Disclosures.

“When I hear people complaining about this stuff, I think they haven’t quite grasped the existential nature of what we’re talking about here – climate is going to impact every bit of your business.

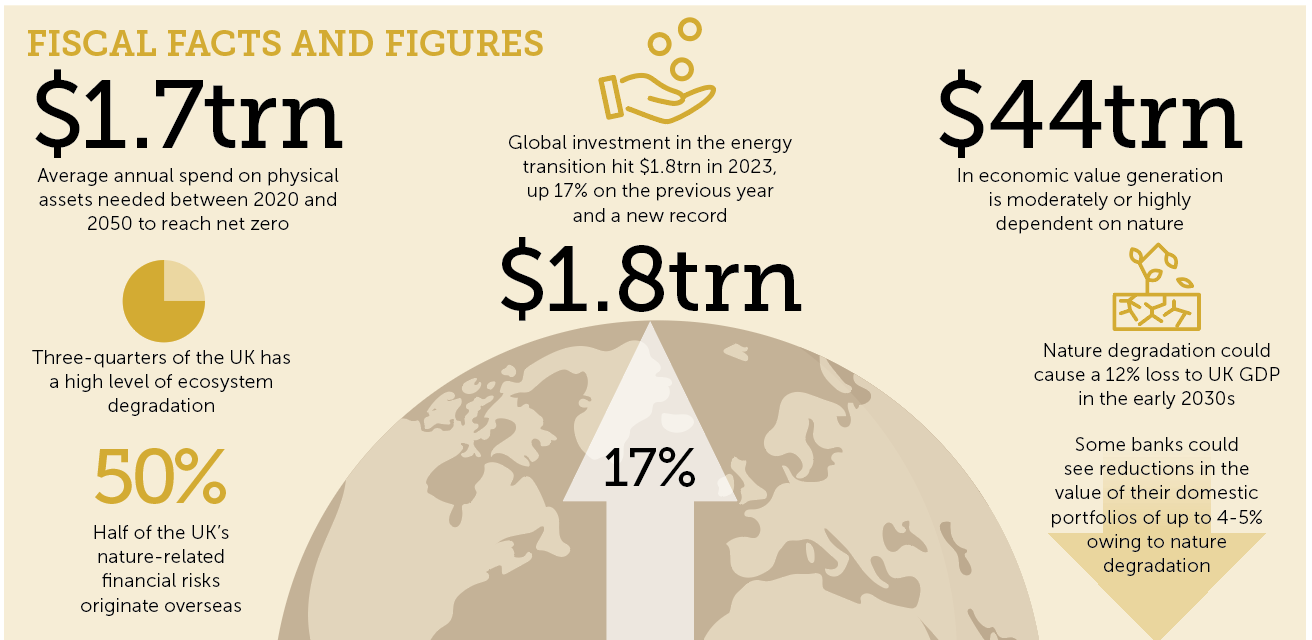

“If we continue on the pathway that we are on with nature depletion, and you throw in an antimicrobial resistance-type epidemic, which we are increasingly at risk of given the way we are treating our soils and agriculture, unfortunately, we could see 12% wiped off UK GDP in the early 2030s. The financial crash of 2008 wiped off about 5%.

“That’s what leaves me scratching my head when I hear people complaining, because climate breakdown is going to be really messy. If you’re under 30, you’re absolutely guaranteed to see this radical destabilisation.”

Despite the success of the Inflation Reduction Act, the US has experienced something of a ‘greenlash’ over the past year as state laws restrict the use of environmental, social and governance factors for public money investments.

“But if you actually take a step back and look at the numbers, there was $1.8trn in clean energy technology invested last year, which is up 17% year on year.

“Then if you look at investments in the UK, and the percentage of inward investment, climate technologies is the biggest category. So you see some of these numbers, and it doesn’t quite square with the media story about how everybody’s moved on.”

Silencing the critics

During her time at Barclays, Thomas and her colleagues helped deliver 11 new green financial products in just 12 months – something that is virtually unheard of – and also won the Barclays Woman of the Year award.

She recalls riding on a Barclays bus during London’s Pride parade one day, and seeing how much people related to the brand.

“I just remember thinking, ‘wow, this really is a brand that impacts people; if I can get us involved in the climate agenda in a massive way, it could really bring people along’. The same goes for all the big, trusted brands.

“The City is full of smart people who are interested in having greater purpose. I think over the next 25 years, all finance jobs will be green finance jobs – they’ll have to be.”

See Assessing the Materiality of Nature-Related Financial Risks for the UK at www.bit.ly/GFI-report-assessing-materiality