Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Curabitur eleifend tortor nec augue pretium

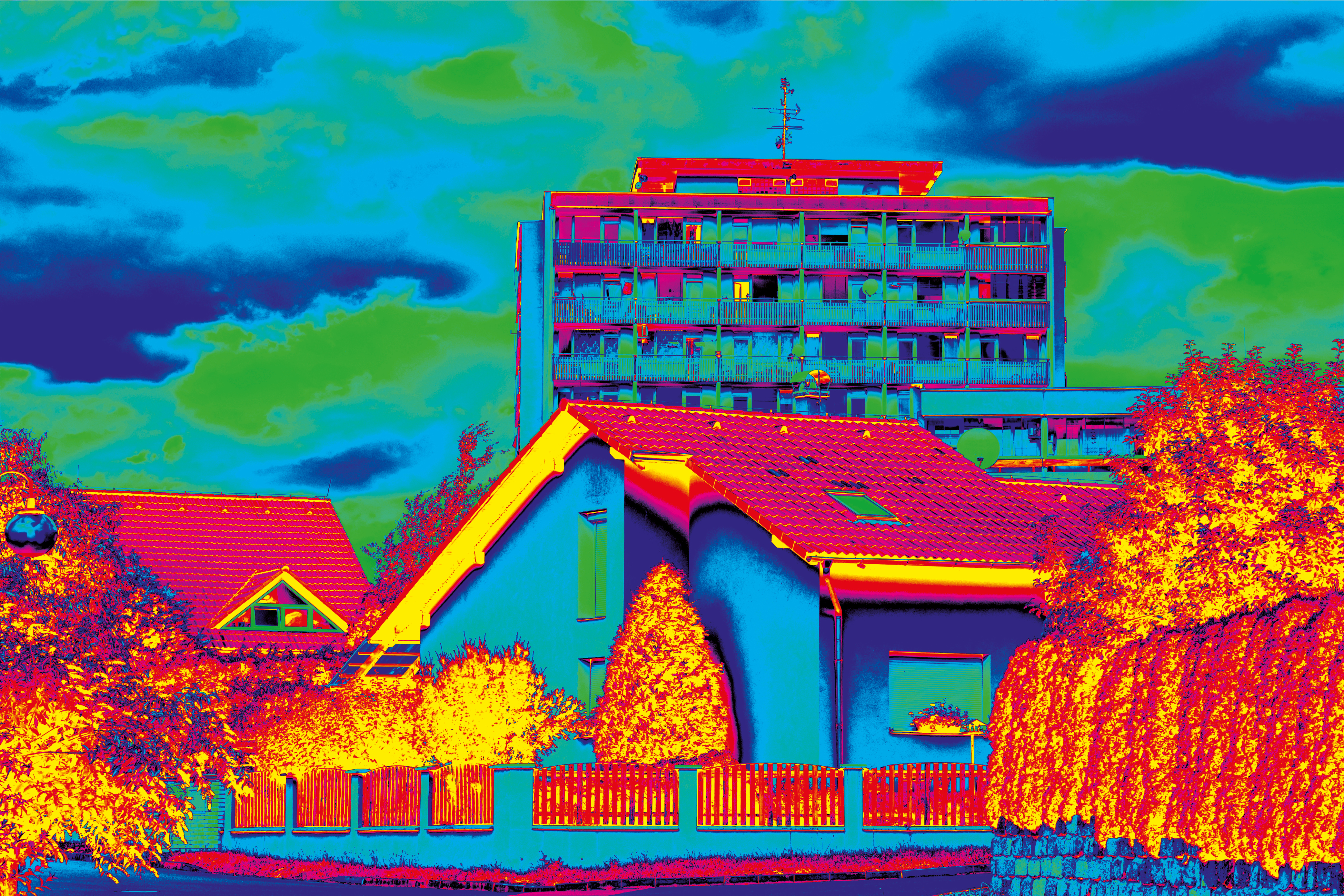

A government-commissioned report on the future heating and cooling needs of the UK housing stock shows that without an extensive programme of retrofit by the 2030s, most UK dwellings will fail current night-time overheating criteria, leaving residents vulnerable to heat-related risks, and highlighting that a more holistic approach to retrofit is needed.

Assessing the Future Heating and Cooling Needs of the UK Housing Stock, published in January, also found that while indoor overheating risk was widespread across the UK, some groups were particularly vulnerable because of underlying health, social, financial and built environment factors, exposing potentially serious inequalities in the impact of overheating on the population.

Overheating occurs when the indoor thermal environment presents conditions that exceed those acceptable for human thermal comfort (thermal discomfort) or may adversely affect human health (thermal stress).

Factors include how the building is designed and constructed, high outside temperatures, solar gains from the building fabric and windows, internal heat gains, and poor removal of excess heat, as well as how the building is used. Overheating can cause discomfort, stress, poor sleep, poor productivity and health risks, including increased mortality.

The UK Health Security Agency predicts that heat-related deaths in the UK will increase significantly in the coming decades. In 2022, a national emergency was declared following the first-ever red warning for extreme heat, and almost 3,000 heat-related deaths were recorded. Such deaths could increase to 4,000+ by the 2030s and 10,000+ by the 2050s.

The causes of this may be complex. A University of Loughborough paper, Overheating in Buildings: Lessons from Research, described a ‘perfect storm’ of interacting factors. These include the changing climate, with hotter summers and heatwaves, urbanisation and urban heat islands, pressure to reduce construction costs, increasing land and property prices, an ageing population, the technical ability to identify and quantify the problem, and a profound social and cultural lack of knowledge about handling excess heat.

It also highlighted that the drive for energy efficiency and decarbonisation may itself have contributed, as more efficient homes resulted in a reduction in the average heat loss of the housing stock, improved insulation standards, and reductions in unwanted air infiltration, but insufficient consideration has been given to summertime heat gains.

The following measures and standards seek to improve the modelling of overheating and address this challenge:

• In TM52: The Limits of Thermal Comfort: Avoiding Overheating (2013), the Chartered Institution of Building Services Engineers (CIBSE) provides a structured methodology for predicting overheating risk in new and refurbished non-domestic buildings, using exceedance, severity and threshold tests.

• TM59 Design Methodology for the Assessment of Overheating Risk in Homes (2017) standardised the assessment methodology for homes and applied the same exceedance criteria from TM52 along with a threshold for bedrooms.

• BREEAM 2018 HEA 04 provides up to three credits for thermal modelling (one credit), design for future thermal comfort (one credit) and thermal zoning and controls (one credit).

• The Good Homes Alliance developed a checklist tool and guidance for identifying and mitigating early-stage overheating risks in new homes.

• There are location-specific policies, guidance and standards, such as the London Plan Policy 5.9 Overheating and Cooling and CIBSE’s TM49 Design Summer Years for London.

• There are further specific guidance standards for different contexts, such as schools (Building Bulletin 101: Ventilation, Thermal Comfort and Indoor Air Quality 2018) and healthcare premises (Health Technical Memorandum 03-01).

However, there is a sense that we do not yet have adequate plans to tackle this. Before the 2024 general election, the Environmental Audit Committee called on the then government to clarify how it planned to mitigate overheating in refurbished buildings, after a response to a committee report did not address this concern directly.

Part O of the UK’s building regulations offers guidance on mitigating overheating in new residential buildings but does not apply to refurbishments. The committee advocated for an extension to Part O to cover refurbishments as the most effective and straightforward way to address this.

The committee highlighted that 4.6 million homes in England already experience overheating in summer, and, if global temperatures warm by 2°C, this could rise to 90% of all UK homes. It concluded that the social and economic case for accelerating heat adaptation measures was “clear-cut”.

So, what must be done? There is no one-size-fits-all solution to modifying the UK housing stock to protect against overheating and reduce inequalities in heating or cooling needs. Diverse building construction ages, typologies and household characteristics make a blanket approach to meeting climate change adaptation and mitigation targets unsuitable. However, overheating mitigation measures must be implemented before the 2030s, especially in the most overheating-prone dwellings.

Limiting and controlling overheating requires a tailored approach, but key measures include reducing solar gain, aiding natural ventilation, looking at how the structural mass is storing and liberating heat, minimising internal gains, effective insulation to services, and addressing occupier behaviour through training and awareness about how the building works and how to manage the internal environment.

The government’s report says that one of the most effective low-cost strategies in reducing overheating risk and associated cooling demand is to install external shutters. We already face a huge retrofit challenge to reduce the carbon impact of our existing building stock, and the Chartered Institute of Building (CIOB) has long called on government to adopt a UK national retrofit strategy to set out how this transition will be achieved.

This is a key area of work for the CIOB policy team, who have made the case for using VAT changes to encourage retrofit over demolition, advocated for a ‘help to fix’ scheme that would provide an interest-free government loan to cover homeowner costs of improvements, and have proposed the deferral of stamp duty on properties that have been purchased with the sole purpose of refurbishment.

Without an extensive programme of retrofit, we are sitting on an overheating time-bomb, and a more holistic approach to retrofit is needed to address this.

As the CIOB’s Retrofit of Buildings technical information sheet makes clear, there will be a range of considerations for any retrofit project, but reducing the risks of overheating should always be a requirement, and all means of minimising summer overheating should be explored.

Other measures such as increasing green spaces in urban areas (parks, urban forests and green roofs) can, of course, also have significant cooling effects as well as providing additional benefits for human wellbeing, air quality and biodiversity. This underlines the importance of a joined-up approach to addressing issues that are so often interconnected and yet too often addressed in isolation.

It remains to be seen how the current government will address this challenge, but its study must provide impetus to inform the development of home energy efficiency and climate adaptation policies, and incorporating a more holistic approach must surely be a top priority.

Amanda Williams FIEMA CENV is head of environmental sustainability at the CIOB

03/04/2025