Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Curabitur eleifend tortor nec augue pretium

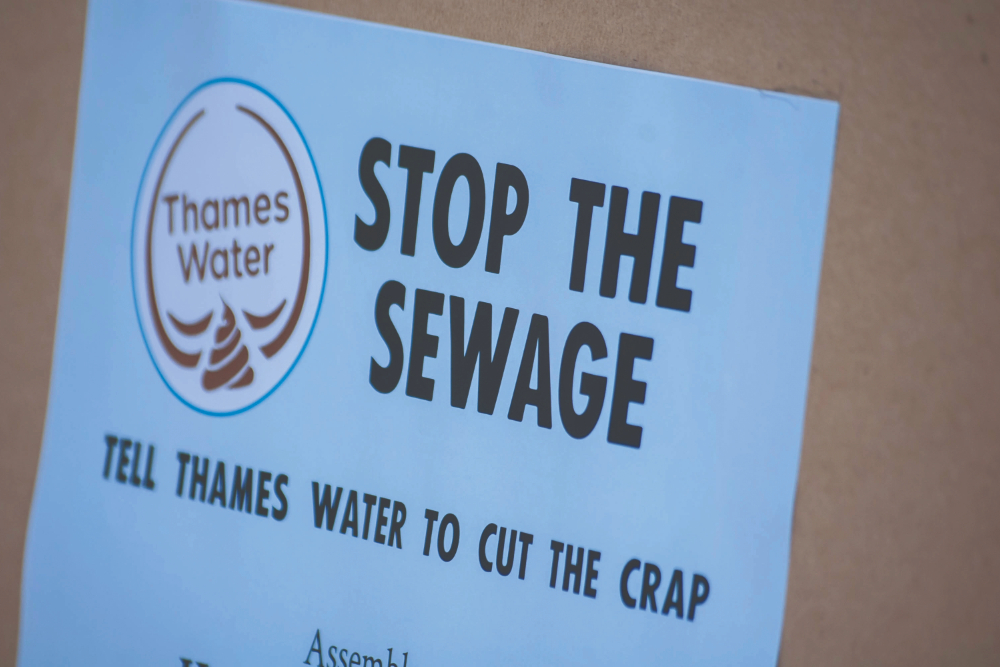

Next month, thousands of people are expected to flood the streets of London to ‘March for Clean Water’ in protest over the dire state of Britain’s rivers and waterways.

They will dress in blue to create a ‘human river’ flowing across Westminster Bridge and into Parliament Square on Sunday 3 November; coinciding with the government’s first 100 days in power.

“The most important issue of our time, without exaggeration, is clean rivers, lakes and seas, and abundant water, and we have neither,” James Wallace tells me just hours after his organisation River Action UK announced the march.

“Literally everything in our economy and society, whether it be jobs, health or food production, relies on abundant supplies of clean water, and they are very much at risk at the moment.”

Indeed, every single river in England is polluted beyond legal limits, with raw sewage spills doubling last year while the profits of water companies soared.

The Water Act in 1989 paved the way for England and Wales to become the only two countries in the world with entirely privatised water systems, although Welsh Water has since become a not-for-profit company.

Although there has been a significant improvement in bathing and drinking water, the UK is at risk of being dubbed the ‘dirty man of Europe’ once again.

There were 3.6 million hours of sewage spills last year, compared with 1.75 million hours in 2022, according to the Environment Agency (EA), while separate analysis suggests that water companies paid out an average of £377 to shareholders for each hour they polluted.

It would be easy to suggest that state ownership would clean up our water, but Wallace believes this argument is too simplistic. “We don’t advocate for a carte-blanche approach for all water companies to be renationalised,” he says. “We don’t think that’s realistic since the challenges that the government faces are manifold. ‘Special administration’ – a form of temporary nationalisation – might be appropriate for failing water companies, but the public must not be made to pay to clear up their mess.”

Climate breakdown, population growth, antiquated wastewater networks and over-abstraction of water have all been blamed for the country’s pollution crisis, but Wallace says that the issue is mainly a symptom of regulatory failure. “Whether it’s the water industry profiteering from pollution, or a lack of enforcement of farming laws, the issue could be resolved if we just regulated properly.”

“Everything in our economy and society relies on abundant supplies of clean water, and they are very much at risk”

A BBC investigation earlier this year found that every big water company in England illegally released raw sewage into rivers and seas in 2022. The practice is allowed during heavy rain via combined sewer overflows (CSOs), which act as a safety valve by preventing sewage from backing up into properties. However, CSOs should only be used under strict permits in exceptional circumstances, and the investigation found that sewage was released 6,000 times into rivers and seas when it wasn’t raining.

“The number of storm overflows is outrageous, but another part of the problem is that the permits rarely require a water company to remove all pathogens, microplastics, antibiotics, and so on,” Wallace explains. “Other waste management industries … are much more heavily regulated.”

Last year, River Action UK launched its ‘Charter for Rivers’, which provides clear, practical steps towards restoring river health; explaining how environmental protection budgets for regulatory agencies such as the EA have fallen by more than 70% in the past decade.

The government has since given the EA powers to hit polluting companies with unlimited fines, and it’s currently conducting its largest-ever criminal investigation into non-compliance.

“Their investigations are under way and preliminary findings have been made, but they take too long and are by no means punitive enough,” Wallace says.

“There’s also great inconsistency. Thames Water was fined £3.3m for a fish kill in 2023 that took six years to prosecute, while Southern Water was fined £330,000 for a fish kill involving a similar number of fish this year.

It was reported in July that water companies could face a “flood” of legal challenges after the Supreme Court ruled that the Manchester Ship Canal Company could sue United Utilities over the alleged release of raw sewage into a canal.

Even cases involving a singular individual could result in legal action. “Someone wrote to me saying they were considering legal action against a water company after she bought a paddle board but the river’s too filthy for her to use it, so she wants to reclaim the cost of the board. That’s just one of many cases. I also know that mayors are thinking of issuing abatement notices (which act like a cease and desist) to water companies that discharge sewage pollution.”

Water companies argue that they won’t be able to do their jobs properly if they have to deal with so many legal challenges. But that’s not an excuse, Wallace argues. “If people are breaking the law, they need to be incentivised to change behaviour – in this case, invest in maintaining and upgrading their infrastructure – or be punished and stopped. It applies to whether you’re speeding, thieving or polluting.”

Thames Water, which is Britain’s biggest water supplier, has eye-watering debt levels, and has said it only has enough funds to continue its operations until next June. It now wants to raise customer bills by more than £260 a year.

“It’s going to be a very tough sell if water companies raise consumer bills while continuing to break the law and reward themselves with dividends and bonuses,” Wallace says. “But there’s a risk that the government could find itself compromised while trying to save water companies from going bust, so it might be tempted to be soft on them in the short term. I think that would be a major political mistake.”

There was much media coverage around pollution in the River Seine during the Paris Olympics, with poor water quality delaying the men’s triathlon race.

“If you’re a big industrial nation your major cities are going to have polluted rivers,” Wallace says. “But having just been to France, I can tell you that the water was in very good condition on the Rivers Rhône, Ain and Isère where I swam with my children. France has 573 official inland bathing water sites that are monitored for swimming.”

Conversely, back in England – where there are only 15 designated bathing sites on rivers – Wallace developed an “agonising” bladder and urinary tract infection earlier this year after swimming in a stretch of the River Thames that Thames Water insisted was safe to swim in.

“Many nations are struggling with pollution,” Wallace says, “but I think it’s fair to say that Britain is by far the worst.

“We want to know who’s actually responsible for people like me who’ve been sick, and all those thousands of rowers, swimmers and other river users who are sick all year. Neither the EA nor the Department of Health seem to show any concern for the risk to human health. With waterborne pathogens causing serious illnesses like blood poisoning, do we have to wait for someone to die before the government acts?”

As we enter the winter months and experience heavier rain, we are likely to see another uptick in river pollution via storm overflows. Water companies have published a £10.2bn plan to end sewage spills and fund infrastructure improvements through to 2030.

However, it’s worth noting that the industry had its debts written off at privatisation in 1989, and borrowed £60bn between that time and

March 2022 while paying out around £72bn in dividends to shareholders. “We’ve been misled,” says Wallace. “We’ve been ripped off, and the very idea that organisations can issue dividends and bonuses while they’re actively breaking the law and polluting is just outrageous and has to stop.”

Water company bosses could face up to two years in prison and be banned from taking bonuses under new government proposals to crack down on pollution in rivers, lakes and seas.

“There are some encouraging signs, but when it comes to banning bonuses for CEOs, that’s a free policy that doesn’t cost anything to implement,” Wallace says. “Sorting out regulations and incentives for farming is not so easy. We need to see the law being enforced to stop the temptation to pollute for profit. Committing extra money to environment land management schemes and to slurry grants to enable more farmers to transition to sustainable manure management would be a good start, as would treating waste as a resource, and encouraging nutrient trading. Ensuring farmers receive a fair price for their produce would be a very welcome move too.

“The first draft of the Water Bill doesn’t impress as there’s no proper mention of regulatory reform and refunding of the EA.”

Feargal Sharkey and Stephen Fry are among the high-profile celebrities supporting this month’s March for Clean Water, and Wallace believes there is huge public support for their key ask to “stop the poisoning of Britain’s rivers” by stopping pollution for profit, reforming the regulators and enforcing the law.

“I was talking to Ellie Chowns, the new Green MP for North Herefordshire, and one of her main electoral messages was water quality. She’s certain she was elected because of that. With many candidates elected on similar promises, we know how important the issue is to people.

“But we need more than soundbites. We need to see actual budgetary commitments, instant and severe legal ramifications, and removing the pollution for profit system. I hope your readers will join us at the March for Clean Water to remind them of the public pressure to deliver.”